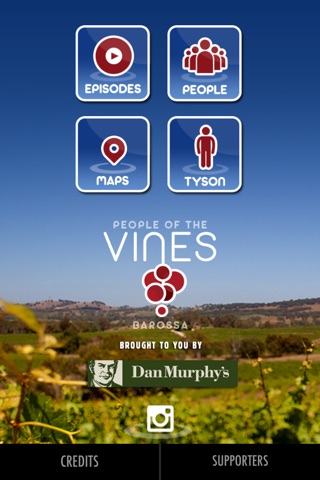

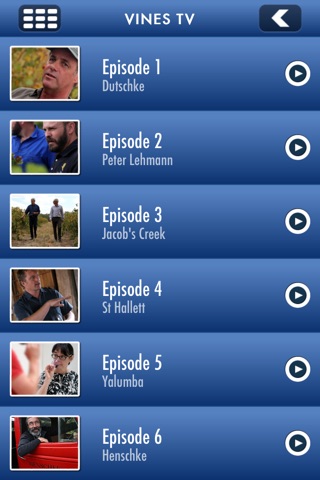

VinesTV app for iPhone and iPad

Developer: Zone4 Digital Media

First release : 05 Nov 2014

App size: 21.86 Mb

There’s much more to the world of the Barossa than it first seems. Turning off the highway, lines of ancient date palms stand as sentinels to guard the road to Seppeltsfield. Spires of fairytale churches stretch heavenward, competing with grand old gum trees on every side. Ancient bluestone cottages watch over lines of primordial vines, their twisted trunks bearing the laughter lines of a century-and-a-half of life in the Barossa.

Century-old barrel halls dot the countryside, ripe with the heady perfume of vintage. The main street of Nuriootpa is filled with the exotic aromas of redgum crackling in the smokehouse at Linke’s butcher. Around every corner, the delicate scent of rose gardens lingers; the Barossa truly lives up to its name, ‘Hill of Roses.’ Night falls and the fragrance of the day dissolves into the crystalline purity of breezes bringing in the twilight from the cool of the ranges.

A local passes by in a 1950s Bedford truck, returning from a day in the vineyards. On another day he’ll polish it up, don his traditional German ‘lederhosen’ outfit and wave at the children from the vintage festival parade.

It’s a different world in the Barossa. At a glance, it might be easy to suppose that these fairytale appearances are no more than a façade to lure the tourists to Australia’s most famous wine destination; an Aussie attempt to replicate kitsch German traditions in a half-hearted fashion. But there’s much more to the Barossa than it might seem.

There is an authenticity to the culture of this place that runs as deep as the roots of its archaic vines. It is a surprising truth that the Barossa’s grand festivals, its traditional produce and its quirky idiosyncrasies are upheld not for the tourists at all, but for the locals themselves. That visitors are welcome to join in is a bonus for the Barossa and a windfall for the rest of us.

Since its settlement in 1842, the Barossa has treasured its German and English heritage, while at the same time cultivating its own unique Australian flavour. “It’s very unusual anywhere in Australia to find a community with such strong links to its European origins,” says Philip Laffer, former Chief Winemaker at Jacob’s Creek. “The Barossa was one of the poorest rural communities in Australia, most people just had a few vines and a cow, and this explains why so many people stayed here – they simply couldn’t afford to go anywhere else.”

And then there is the wine. That potent, deep purple glue that binds this community together. “There are very few communities that are driven around one thing,” says Wolf Blass Chief Winemaker, Chris Hatcher. “In the Barossa, wine is at the core of everything.”

More than any other Australian wine region, the Barossa is its own. There is no other precedent to which it aspires, and there is no Old World wine to which it pins its allegiances. In its own inimitable way, the Barossa marches to the beat of the drum of its own Oom-pah band.

If anything is new in the Barossa today it is a renewed recognition of the old. Winemakers have launched their ‘Barossa Old Vine Charter’ to recognise and protect the oldest Shiraz and Cabernet vines in Australia, and most likely the oldest Grenache and Mourvèdre, too. These rank among the oldest vines in the world.

Wrapped in a plethora of layers of heritage is a unique Barossa that is today one of the most remarkable communities that you could visit anywhere in this country.

In its places, faces and never-before-told stories, People of the Vines will take you into vineyards, the wineries, the homes and the lives of the Barossa, exploring the inside stories, leading you through a behind-the-scenes tour and introducing the characters of the Barossa. These are the People of the Vines.